- Home

- Dobyns, Stephen;

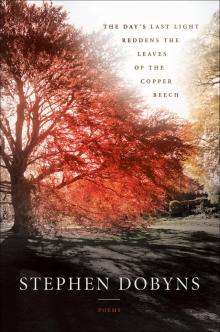

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech Read online

The Day’s Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech

BOA wishes to acknowledge the generosity of the following 40 for 40 Major Gift Donors

Lannan Foundation

Gouvernet Arts Fund

Angela Bonazinga & Catherine Lewis

Boo Poulin

POETRY BY STEPHEN DOBYNS

The Day’s Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech (2016)

Winter’s Journey (2010)

Mystery, So Long (2005)

The Porcupine’s Kisses (2002)

Pallbearers Envying the One Who Rides (1999)

Common Carnage (1996)

Velocities: New and Selected Poems 1966–1992 (1994)

Body Traffic (1990)

Cemetery Nights (1987)

Black Dog, Red Dog (1984)

The Balthus Poems (1982)

Heat Death (1980)

Griffon (1976)

Concurring Beasts (1972)

Copyright © 2016 by Stephen Dobyns

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition

16 17 18 19 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For information about permission to reuse any material from this book please contact The Permissions Company at www.permissionscompany.com or e-mail [email protected].

Publications by BOA Editions, Ltd.—a not-for-profit corporation under section 501 (c) (3) of the United States Internal Revenue Code—are made possible with funds from a variety of sources, including public funds from the Literature Program of the National Endowment for the Arts; the New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency; and the County of Monroe, NY. Private funding sources include the Lannan Foundation for support of the Lannan Translations Selection Series; the Max and Marian Farash Charitable Foundation; the Mary S. Mulligan Charitable Trust; the Rochester Area Community Foundation; the Steeple-Jack Fund; the Ames-Amzalak Memorial Trust in memory of Henry Ames, Semon Amzalak, and Dan Amzalak; and contributions from many individuals nationwide. See Colophon on page 116 for special individual acknowledgments.

Cover Design: Sandy Knight

Cover Art: Copper Beech 62", copyright © by Benjamin Swett

Interior Design and Composition: Richard Foerster

Manufacturing: McNaughton & Gunn

BOA Logo: Mirko

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dobyns, Stephen, 1941- author.

Title: The day’s last light reddens the leaves of the copper beech: poems / by Stephen Dobyns.

Description: First edition. | Rochester, NY: BOA Editions Ltd., 2016.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019091 (print) | LCCN 2016024012 (ebook) | ISBN 9781942683162 (paperback: alk. paper) | ISBN 9781942683179 (ebook)

Subjects: | BISAC: POETRY / American / General.

Classification: LCC PS3554.O2 A6 2016 (print) | LCC PS3554.O2 (ebook) | DDC 811/.54—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019091

BOA Editions, Ltd.

250 North Goodman Street, Suite 306

Rochester, NY 14607

www.boaeditions.org

A. Poulin, Jr., Founder (1938–1996)

Shimer friends: Peter Cooley and Peter Havholm

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One

Stories

Stars

Wisdom

Parable: Horse

Mrs. Brewster’s Second Grade Class Picture

Furniture

Water-Ski

Leaf Blowers

Parable: Heaven

Good Days

Part Two

Sixteen Sonnets for Isabel

Monochrome

Song

Technology

Skyrocket

Lizard

Swap Shop

Alien Skin

Pain

Niagara Falls

The Wide Variety

Skin

Never

Casserole

Inexplicably

Prague

Gardens

Part Three

The Miracle of Birth

Fly

The Inquisitor

The Poet’s Disregard

Parable: Gratitude

Sincerity

Hero

Statistical Norm

Turd

Parable: Friendship

The Dark Uncertainty

No Simple Thing

Part Four

Reversals

Narrative

Determination

Jump

What Happened?

Philosophy

Melodrama

Exercise

Failure

Constantine XI

Literature

Jism

Valencia

Thanks

Part Five

Persephone, Etc.

Crazy Times

Parable: Fan/Paranoia

Winter Wind

So It Happens

Tinsel

Future

Parable: Poetry

Scale

Cut Loose

Recognitions

Laugh

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Colophon

PART ONE

Stories

All stories are sad when they reach their end.

The rain comes; the night falls; Malone dies alone.

With little bites, the pragmatic devours the idealistic.

A bit of ash, a grain of sand; dust blows down the avenues.

Only yesterday the world shook its pom-poms;

roads extended their promise under an azure sky:

here an oasis, there an oasis, fat dawdles in between.

Pulled down from their branches, the hours

were quickly tasted and tossed away. What’s this,

clouds on the horizon, or do we need glasses?

Between the countries of Arriving and Leaving,

no frontier, no change in the weather till later.

The murmuring, unruly mob lumbering behind;

the walls each morning yellowed by setting sun.

Stars

The man took the wrong fork in the road.

It was out in the country. They saw

no signs. It was getting dark. They began

to blame each other. Should they keep

going straight or should they turn around?

They drove past farms without lights.

The man said, If we reach a crossroad,

we can just turn right. His wife said,

I think you should turn around. The man

was driving. They kept going straight.

There’s got to be a road up here someplace,

he said. His wife didn’t answer. By now

it was pitch black. In their lights, the trees,

pressing close to the road, looked like people

wanting to speak, but thinking better of it.

The farther they drove, the farther they got

from one another, until it seemed they sat

in two separate cars. Who’s this person

next to me? This thought came to them both.

They weren’t newlyweds. They had children.

He’s trying to upset me, thought the woman.

She thinks she always knows best, thought

the man. They were on their way to dinner

at a friend’s farmhouse in the country. Now

they’d be late. It would take longer to go back

than to go straight, said the man. The woman

knew he hated it when she remained silent

so she said nothing. The woods were so thick

one could walk for miles and never get out.

The stars looked huge, as if they had come down

closer in the dark. The woman wanted to say

she could see no familiar constellations,

but she said nothing. The man wanted to say,

Get out of the car! Just to make her speak!

Where had they come to? They had driven

out of one world into another. They began

to recall remarks each had made in the past.

Only now did they realize their meanings,

hear their half-hidden barbs. They recalled

missing objects: a favorite vase, a picture

of his mother. How foolish to think they had

only been misplaced. They recalled remarks

made by friends before the wedding, remarks

that now seemed like warnings. Ice crystals

formed between them, a cold so deep that only

an ice ax could shatter it. Who is this monster

I married? They both thought this. Soon they’d

think of lawyers and who would get the kids.

Then, through the trees, they saw a brightly lit house.

They had come the long way around. The man

parked behind the other cars and opened the door

for his wife. She took his arm as they walked

to the steps. They heard laughter. Their friends

were just sitting down at the table. On the porch

the man told his wife how good she looked,

while she fixed his tie. Both had a memory

of ugliness: a story told to them by somebody

they had never liked. As he opened the door,

she glanced upward and held him for a second.

How beautiful the stars look tonight, she said.

Wisdom

With the door shut the child sat in the closet

with his fingers pressed in his ears. Tell me

the truth, wasn’t it wisdom? Hadn’t he had

a sudden insight into the nature of the world?

One time my stepson in third grade refused

to take any more tests. His reason? If you take one,

they’ll only give you another. Better call a halt

right now. He had caught on to the grownups’

stratagem to drag him into adulthood. What

was in it for him? he asked. Nothing nice.

Likewise the boy in the closet had become

temporarily resistant to the blandishments

of the world. Two hours later, his own body

turned against him and he crept downstairs

to dinner. But when his parents pointed out

the joys of growing up, he remained in doubt.

Who knew how the thought had come to him?

TV, a friend’s chatter? Perhaps he had seen

a picture of a conveyor belt. Click, click—

so he’d go through life until he was dumped

on a trash heap. Or perhaps he had deduced

what he was leaving behind, the shift from

innocence to consequence, from protection

to fragility. Fortunately, stories like the boy

shutting himself up in the closet are scarce,

and his parents joked about it to their friends.

By now, I don’t know, he’s on his second or

third marriage, has a job that’s made him rich,

but that time in the closet, five years old and

calculating what life was destined to deal out,

how different it must have seemed from what

he had ever imagined, so he made his decision

and crept into the closet, wasn’t it wisdom?

Parable: Horse

He peered into the bar mirror over the bottles

of gin and whiskey. Yes, he thought, he really

did have a long face. Why hadn’t he noticed it

before? But looking out of his moony eyes,

he rarely wondered how others saw him, since,

apart from mirrors, he rarely saw himself.

Sure he was tall, no surprise there. Walking

along city sidewalks, he felt that was why people

slid to a stop when they saw him. But perhaps

it was his face that upset them, its odd expanse,

tombstone teeth, satchel mouth, black rubber lips.

People gawked and, glancing back, he saw

they were gawking still. None of this was new.

Yet each occasion once more fueled his sense

of isolation, which had begun at birth and came

from being an only child. He had no memory

of his father. His mother ran off after a few weeks

and he’d been raised by strangers. Stubbornly,

he worked to be strong, get on with the business

of living, to focus his thoughts on the road ahead.

But then a cruel wisecrack or brutal snicker

would tumble him back to the beginning again,

the self-doubt and crushing solitude. Did it really

matter if he had a long face? But it wasn’t just that,

it was his whole cluster of body parts. Alone they

might have been fine, even the boxy feet. Then,

when all joined into the oneness that was him,

it changed. Not only did people stare, they looked

offended; as if his very presence upset their pride

and sense of self-worth; as if they were saying, How

can it be good fortune for us to walk here, if you

walk here as well; as if to see him and smell him

lessened them as human beings. Soon they’d brood

about their failings: broken marriages, runaway kids.

Was this his only power, to make others feel lesser?

How many of these downcast do we see on the street

whose insides are marked by scars, who show off

their apparent good cheer and lack of concern only

to conceal their fears? And even if we saw them

what could we do? The bartender coughed to get

his attention, half-grinning, half-appalled.

Why shouldn’t he stay? He had no one to visit,

no place to go; he had only these long afternoons

in anonymous bars with the televisions turned low.

Give me a Jack Daniels, he said, and put it in a bowl.

Mrs. Brewster’s Second Grade Class Picture

That’s me, standing in the third row

with a wiseacre grin, skinny and blond,

taller than the others. Of the rest, George

and Jane, Jacqueline and Tom, a class

of sixteen and I recall nearly all the names:

the boys in white shirts or plaid; the girls

in skirts and bobby socks. Mrs. Brewster

stands to the right, dark hair, a benign smile.

She, who I’d thought old, looks about forty:

Bailey School, East Lansing, Michigan.

By now roughly sixty years have passed,

while the lives that, in 1948, were scarcely

at the start of life have almost completed

their separate arcs, if they haven’t done so

already. Strange to think that some are dead.

A few of these children had great success,

a few had moderate triumphs, others

were dismal failures. Some were granted

happiness each day they spent on earth;

some felt regret with every step. I know

nothing of how their lives turned out.

Look at Margaret sitting cross-legged

in

the front row in a light-colored dress.

The black and white photograph can’t

do justice to her fine red hair. A smile

still uncorrupted by appetite or cunning,

no telling how long it retained its luster.

But all must have pursued life with various

degrees of passion, arrived at decisions

they felt the only ones possible to make.

How many would now think otherwise,

that the indispensable trip to Phoenix

might as easily have been to New York,

that the choice of a career in law might

just as well have been a job in a bank?

What is needed after all? Which choices

are the ones really necessary? Could I

have been as happy as a doctor or even

a cop? No burning passion lies hidden

in these faces, all that came later, if it

came at all. But how bright and eager

they appear, how ready to get started.

One morning Mrs. Brewster gave us a treat,

showing her slides of Yellowstone Park.

In the dim light of drawn shades we stared

at a buffalo calf crossing a brook, a bald eagle

perched on a dead branch, Fire Hole River,

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech