- Home

- Dobyns, Stephen;

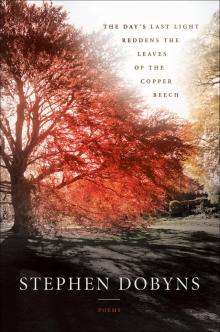

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech Page 2

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech Read online

Page 2

Mystic Falls, Old Faithful of course. How strange

these places looked compared to where we lived.

Were these the wonders we’d been promised?

At the water’s edge a grizzly devours the carcass

of an elk; a black wolf creeps out of the pines.

Furniture

How devious is our perception of rapidity.

The facial movements of human beings

skitter about like the flight of swallows.

The facial movements of tables and chairs

are more discreet in their outward gestures.

Such is the case with all inanimate objects.

The foolish would say that stationary objects

remain stationary. This is false. They move

a little faster than raindrops sculpt a rock.

Why hurry? What is won by hasty action?

This is why you never see a chair quarreling

with another chair; rather, they contemplate

the virtues of passivity, which is the reason

chairs are so very kind, tables also. They see

human beings as only a blur as we rush and

rush and then arrive at our end. They see us

as we might see a speeding bullet. You ask

what persistent thought has brought them?

They arrive at certainty before, not after,

an event. They have solved the problem

of unexpected results from random causes.

They have discovered the square root of pi.

Most of all, their work has shown them the path

of inflexible humility. Humbly, they let us

knock them about, stack them in a corner,

sell them from an auction block. Yet always

they offer us the other cheek. Let us study

their calm to become stronger, hiding desire

as disinterest, guile as composure. But no,

they don’t like us; they have never liked us.

Water-Ski

The gift of putting something down, he had yet to discover it—letting it slide from his grip. You’d think it would be easy; an opening of the fingers and the person, humiliation, failure would float away. Instead, he kept going over the details, the variations and possibilities; what would have happened if he had done this or that. And so the ill-fated event occurred not once but a thousand times. He recalled those occasions years before when he’d tried to water-ski. There was always a moment after he fell when he hesitated to release the rope and was dragged roughly over the surface of the water. It was like that now. Let go, let go, he shouted to himself, as the hard surface of what he called his life pummeled and raked his skin.

Leaf Blowers

That autumn morning he awoke to the crying

of lost souls that quickly changed to the roar

of leaf blowers up and down the block. Still,

the lost souls hung on, although only as idea,

as if the day’s cloudy translucence had become

the gathered dead circling the earth. Nothing

he believed, of course, but the thought gave flesh

to the skeletal lack, who assumed their places

on imaginary chairs and couches: acquaintances,

old friends, relatives, as impatient as patients

in a doctor’s waiting room, an internist late

from a martini lunch.

Yet it was him, his attention

they seemed to crave. Did it matter they were false?

They were real as long as he imagined them.

And their seeming need for him, surely the opposite

was true, as if they formed the ropes and stakes

tying down the immense circus tent of his past,

till, as he aged, the world existed more as pretext

to bring to mind the ones who had disappeared.

This morning it was leaf blowers, in the afternoon

it might be something else, so as time went by

the palpability of what was not, came to outstrip

the formerly glittering quotidian, till all was seem,

seem, ensuring that his final departure would be

as slight as a skip or jump across a sidewalk’s crack,

perhaps on a fall morning with sunlight streaking

the maples’ fading abundance. Afternoon, evening,

even in the dead of night, waking to clutch his pillow

as he slipped across from one darkness to the next.

Parable: Heaven

At first it seemed as nice as the real Heaven—

a little eating, a little fucking, a little nap,

then a little eating again, the cycle repeating

over and over. But maybe Forever would be

too much, even a century would be a struggle,

even a year. In time the fun would begin to pale—

a little eating, a little fucking, a little nap. Sure,

the others were terribly nice, if not too quick

in the head at least. Lush fields, oaks in full leaf—

a veritable Garden of Eden. In the nursing home,

when she and Rosie had discussed the option

of Heaven, each swore if she were taken first,

she’d come back to tell the other what it was like.

But Heaven meant being a rabbit in Wisconsin.

Wouldn’t she be ashamed to visit Rosie now?

Even if she hurried back to the nursing home,

she was sure to be caught and wind up in a stew.

Negative thoughts, too many negative thoughts:

It was her duty to focus on the bright side of life.

Who cared if she’d had affairs, lied to her friends,

took money from the till or keyed the car doors

of folks she disliked, wasn’t this human nature?

After all, millions were clearly more sinful than she.

So it stood to reason she’d be forgiven. But when

a hawk snatched up a new friend, she understood

why this spot meant giving birth to a constant

supply of bunnies—a little eating, a little fucking,

a little nap. No wonder her friends were jittery

and their noses twitched; no wonder they were

speedy runners with foxes and coyotes lurking

in the underbrush. Eating, fucking, and napping,

wasn’t it just self-medicating? So as she popped

out litter after litter, she began to ask: When

would it happen to her? When the fox’s teeth

clamped vise-like on her neck or she heard

the owl’s plunging rush of wings, would she

then find herself in the fleecy clouds of Heaven—

the hallelujahs, perpetual singing, the regular sex—

or had she mistaken her location from the start

and she’d come back as a spider, maybe a snake?

Good Days

Jack McCarthy, Stand-Up Poet, 1939–2013

It had been one of those good days with friends

and now we were sitting around the bonfire

telling stories—a circle of light within the dark.

The wind through the trees above us sounded

like faraway conversations, perhaps the talk

of friends around bonfires in the past. Some

were drinking, some not. Some leaned back

on their elbows, some sat cross-legged.

You know how it is: your face grows hot,

your back turns cold. As time passed, one

by one, men and women got to their feet and

walked into the night. Yes, that’s how it was.

Part Two

Sixteen Sonnets for Isabel

Monochrome

The day I learned my wife was dying

it was September. Trees were green,

now they turned brown; flowers dimmed;

to rec

all their color seemed a mockery.

This was the first of the changes, then came

the slow shift to monochrome,

as all of nature commenced to bleed out

and take on the face of an overcast sky.

Unaccountably, people kept walking around.

They shopped; they partied. I called to them:

Hide in your basements! Try to stay warm!

Some laughed; some scratched their heads.

Then I knew the world wasn’t broken;

my eyes were broken.

Song

The day I learned my wife was dying

is farther away than the fall of Rome

and as close as the next second.

It’s dread promise fills every moment.

Birds mouth their songs; I hear no sound.

The air is heavy; they can hardly fly.

Everything is upside down. Sparrows

and robins line up on the wires. Then one

tumbles to the ground. Some days, I think,

I’m only a half step from surrender. In Rome,

songbirds’ tongues were a delicacy. Eating them,

people mouthed their songs, hoping to sing,

as I do now. Grunts, rasps, croaks, gasps:

this isn’t their song; it’s my song.

Technology

The day I learned my wife was dying

she and I changed from one statistic

to another. Computers made the adjustment,

hummed a little, then settled down again.

The hum conveyed no misery or grief,

which was a big step for us all, because

formerly a clerk marking a sheet might

recall his own familiar absences and blot

his paper with a salty drop. How foolish

life was in the old days. Technology makes

it simpler; nasty events can be modified

by smart machinery and nothing need be

“hands on” anymore. With a single keystroke,

the worrisome page again becomes virginal.

Skyrocket

The day I learned my wife was dying

I tried to think it was a kind of hurrying-up,

since, of course, our first breath after birth

is the start of our dying. I told myself

death is part of life. I was full of lies.

I tried to put something between me

and the fact of her illness: maybe a wall,

maybe the obliteration of perception.

Nothing worked. As the world got dimmer,

her death grew brighter, nosier; it zigzagged

about the house like a frantic rocket. That’s

how it seemed. I wanted a little quiet

for productive thought, but as time passed

I knew it was best to keep my mind blank.

Lizard

The day I learned my wife was dying

I thought, What about me? Then I grabbed

the virtual hammer I always keep with me

and whacked myself over the head.

I was like a pup tent in Manhattan.

I wasn’t the subject of the sentence;

I wasn’t even in the sentence. A beer

can bobbing in the ocean, that was me.

Her illness eased its lizard body into our home,

slid its vastness across chairs and left slime

on the walls till nothing was familiar anymore.

It’s red tongue flicked and we ran. My wife didn’t run.

She tried to teach us acceptance. But we, as foolish

as ever, wanted tools to fight it, not acceptance.

Swap Shop

The day I learned my wife was dying

the knowledge became a leash clipped

to my collar, a leash in the paw of her illness,

which rose tall above me; and if I thought

of a book, ball game, or chicken dinner,

the leash would be given a sharp yank

to show who was in charge, and whack me

with the fact of her dying. I wore the leash

all day; I wore it at work and when I slept;

I wore it in the shower. A single step

in the wrong direction put it in action

and I’d be flat on my back. You know those

dodgy trade-offs in swap shops? It was like that:

all my thoughts traded for the one I dreaded.

Alien Skin

The day I learned my wife was dying

I began to hear of her illness all over.

People in carwashes and barbershops had it,

friends, acquaintances, even enemies had it.

On TV it was the topic of panel discussions;

its name lurked at the foot of all conversations.

I felt confused; it was as if these others existed

to diminish my wife’s individual pain, as if

her illness were less serious by being in a crowd.

But we knew hers was the worst. All the family

knew that. And what we knew was like a layer

of alien skin and we scratched at its scaly presence.

But it never bled, no matter how hard we scratched;

rather, to mock our good health, it turned rosy.

Pain

The day I learned my wife was dying

I thought of the interior pain of those

who loved her, starting with me.

But no x-ray machine would show it;

pills, operations, nothing could prove it.

The people who loved her would look

perfectly healthy. I’m not really, I’d say,

I’m really very sick. Ditto all the others.

Perhaps we could hold up signs describing

just where we hurt; or wrap ourselves

in bloody bandages, use crutches and canes

to explain the degree of our interior pain.

Friends might guess my mountain of loss,

but I’d buy ads on TV to tell strangers.

Niagara Falls

The day I learned my wife was dying

I thought of all the words we’d never speak.

Not just I love you or let’s go for a walk,

but complaints and words from fights.

How much I’d give to have her to tell me

take out the garbage, pick up your books!

I’d be eager to see her angry again; I’d accept

any slight or defamation of character.

But like the world on old maps, up ahead

loomed a cataract. As at Niagara, folks

with telescopes might watch us float by

as we, in our barrel, bobbed toward it. How

feeble is language! Where were the words

to turn this to a story to make her laugh?

The Wide Variety

The day I learned my wife was dying

I wanted to think it was somebody’s fault.

Big business, chemical toxins or perhaps

it was the fault of the man up the street.

If that were the case, I’d give him a smack.

But I had no one to blame; no one to punish.

So what could I do with my anger? Could I

hurl stones at the sky, polish my whimper?

It’s depressing to have no one to blame,

to sit beside her with no solution, nothing

to fix. I needed villains, like demons in antique

paintings plaguing a saint. But these days

that wide variety is internalized: the vicious,

good and malignant, all find a place within us.

Skin

The day I learned my wife was dying

I touched the back of my hand gently

to her cheek. How warm it felt.

What will it be like when it’s not?

To find out I took bags of green beans

from the freezer, stuck my

finger

in ice cream to feel the cold, but

I couldn’t get the temperature right.

But no, all that’s a lie. How paralyzing

becomes bad news. I felt I knew exactly

what her skin would be like. I couldn’t

stop thinking about it. And whatever

I guessed, it would be worse; and can I

guess the color? There will be no color.

Never

The day I learned my wife was dying

I went to read about volcanic eruptions,

earthquakes, fire, bloody war, and murder.

I wanted to discover the most awful, because

I knew her death would be worse than that;

and even crueler would be her absence, not

for a day or a year. It meant not coming back.

That was what I couldn’t imagine. How many

days in Never? How many times would we

hear a car and think, That’s her, or hear

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech

The Day's Last Light Reddens the Leaves of the Copper Beech